I was around twelve years old when music really got me, when it became more than just auditory scenery in my life. Yeah, I’d liked music before, I’d sung along to the catchiest of the records my parents played, got ear-wormed by pop songs on the radio, and madly danced in front of the humungous, fizzing television when Top of the Pops came on each Thursday evening…but it had all been part of wider play, just childish fun. And then suddenly, like a emotion bomb going off in my pre-teen heart, it wasn’t…it was EVERYTHING.

The first record that made my insides feel floaty and my brain race was ‘The Wild Ones’ by Suede; I’d seen the video on The Chart Show, a Saturday morning Top 40 countdown that always managed to shoe-horn a few credible, indie releases into the parade of boy-bands and euro-pop each week. Thirty years on, I realise that that sensation in my body, that weird mix of wanting to cry and scream, was actually what love feels like, real grown-up human love. Brett Anderson and Bernard Butler broke my heart and woke me up in just over 4 minutes.

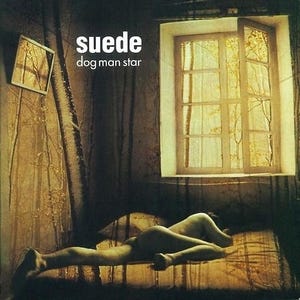

That afternoon I took all my hard-earned pocket money and went with my mum on the bus into Oxford, to the seemingly cathedral-like HMV on Cornmarket Street, to buy the newly released, sophomore Suede album ‘Dog Man Star’. I could tell she was unsure when we found it at the front of the shop, the cover image being a bare arsed person lying in a distinctly broken fashion on a bed, but she allowed it to come home. I remember being both mesmerised and appalled by the booklet art, a collection of strange, dark images that spoke of another world far away from village life and year 8 school days. And the music was similarly grainy and seedy; it confused me, it almost terrified me, but it also caused that previously unfelt buzz in my brain. I played that CD to death over the coming months, and I can still now tell you the exact track order, and possibly even the studio personnel written in the liner notes. It dug its claws in deep and I liked it.

But at just twelve years old, record shopping was something rare and mostly unreachable. My 7 day a-week paper round only paid £11 total (you got a little extra danger money for the heavier Sunday broadsheets…), so I could, at most, buy two or three albums a month, but only if I excluded books and sweets and clothes and incense and magazines and all the shit someone on the cusp of adulthood absolutely, 100% needed in order to survive. So the day my parents introduced me to the Oxford Central Library Music Department was a great day indeed. For £1 a week I could borrow an album, take it home and make an absolutely atrocious, hissy tape copy on my tiny Sony boombox. I call this Home Counties pirating. As I also now needed to buy stacks of C-90 cassettes to conduct my shady business, I allowed myself roughly 8 CD loans per month, which left enough money for copies of NME and Melody Maker, occasionally Kerrang! magazine if I was feeling a little heavier.

Oxford Central Library in the mid-nineties was much like a comprehensive secondary school, all shiny orange wood and plastic carpets, so it immediately felt weirdly welcoming and familiar. My clear memory is Saturday morning sunlight coming in through the big glass doors, the bored security guard in place at his desk in the atrium, and the staircase winding round and up to the first floor, where the music library lived. In a time well before downloads or streaming or even Napster and Limewire, this was an absolute goldmine. I mostly worked off the weekly music magazine reviews to find things, but on the odd occasion got tricked by some amazing artwork or fancy packaging. Some of the records I borrowed there remain absolute, life-long favourites: ‘No Need To Argue’ by The Cranberries, ‘Spirit of Eden’ by Talk Talk, ‘Grace’ by Jeff Buckley, ‘Pink Moon’ by Nick Drake, ‘Closer’ by Joy Division, ‘Disgraceful’ by Dubstar, ‘In Utero’ by Nirvana etc. Sometimes the gushing NME reviews built things up just a little too much, an overly poetic journalist describing an album as ‘a catalogue of dreams, a deep dive into perfect darkness’, or something along those lines, would conjure up such magic in my head that the reality could only ever disappoint. I remember waiting over a month for the library to get in a copy of ‘Akathisia’ by the US band Hovercraft, an album that Melody Maker had lauded as near perfect, majestic and soaring. I hated it, it didn’t match the sound in my head at all…but I still taped it, I still tried it a few times before I reused that cassette…

And that’s the amazing thing about how we used to consume and value music. I was happy, no…delighted, to traipse into Oxford on a weekly business in order to find new musical obsessions. I respected and enjoyed the process of reading about music, then listening to a record from start to finish; I researched my choices and I pushed through uncomfortable first listens and found something I loved. I took care of my CD collection like it was rare art. I even broke the fucking law in order to have great music in my life! I’m gutted that my children will never know that feeling, that near obsessive urge to hunt out song treasure and share it with your tiny contained world. We’re so blinded by choice, we have the literal entirety of music history at our fingertips and it’s made us so complacent and bored…and a little ungrateful. I miss the Music Library. I miss the wait and the anticipation and the revelation of a first listen. I miss the NME and Melody Maker. I really, truly miss being limited. Technology makes our lives better and easier in so many ways, but all I want is to feel that feeling of wanting music again. How do we get back there? I bet we can, if we try…

My reworking of The Cranberries’ ‘No Need To Argue’ is out on July 16th, you can pre-save HERE

I identify and concur with every word you wrote Richard.

In my case such libraries were unavailable so it became a system of buying cassette tapes and giving them to friends to record albums I was unable to afford or had no access to. I would do the same for them. Christmas and birthday presents for friends were compilations of tracks I thought they should hear and would like.

In later years such compilations became CD-Rs and they would convey to the recipient something I myself could not put into words let alone song. I now look at those compilations with immense fondness and nostalgia, grateful of the evergreen gems I chose to include.

Off topic but related is that some of my early tapes made for friends featured tracks by Mott The Hoople and this week I was greatly saddened to hear of the passing of Mick Ralphs, the original Mott lead guitarist and sometimes vocalist. Following Mott he formed a very successful band known as Bad Company. A Mott track titled ‘Thunderbuck Ram’ was often a secret weapon on those tapes I made. I was sure it would be unfamiliar but immediately loved. The only reason I had a copy is because my father brought it back for me from the US on one of his many trips there. It was never released in my native Australia.

The album was ‘Mad Shadows’. The cover was a dark mystery and the songs were Dylanesque in parts and heavy in others, a blend that I found infinitely exciting. Only two original members of Mott remain, the eternally young and gifted songwriter Ian Hunter and organist Verden Allen. RIP Ralpher.